Wilderness

Wilderness

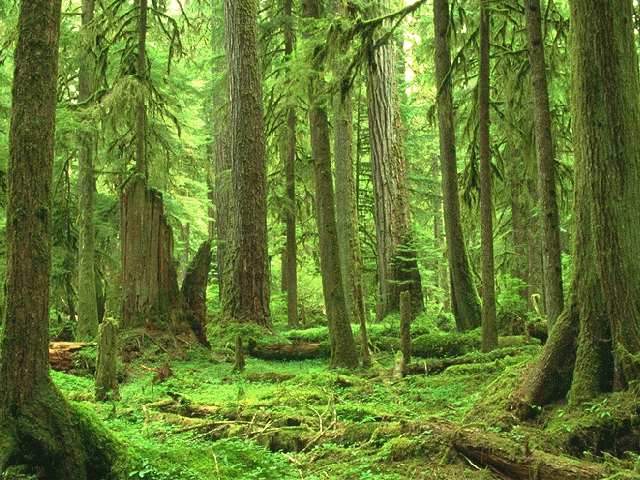

SCENES IN THE FOREST.

MANY are the pleasant thoughts linked by our memories of childhood, with the wild woods. After the long winter, what a relief it was to hear the loud "popping" of the trees as the frost yielded his hold. A hopeful sound too, was the long-drawn "pee de" of the titmouse, brave little bird, that with nut-hatch and blue-jay dared to brave the northern winter; that felt the first south wind, and heard in the sugar-camp the ringing of the "tap-ping gouge."

Thousands, aye, sometimes millions of woodpigeons flew backward and forward as if to distribute the blessings of spring; and when at last came the first mild showers, the moistened woods grew fragrant and green.

The little Spring Beauty and Adder's-tongue, the Hepatica and up rolling feathery ferns were beneath our feet, and the white banners of the dogwood overhead. With the evening, came the plaintive notes of the whippoorwill, starting mournful echoes into life among the hills.

Summer came, with its endless variety of birds and flowers and shimmering leaves. In the green summerwoods every motion is graceful, every sound agreeable, every line a line of beauty. Each leaf and branch is swayed in graceful curves. Each sound, from the whispering of the wind in the pine tops to "the falling of the oak in the stillness of the forest," affects us with a feeling of admiration or sublimity.

Here is growth of various kinds, growths of a single night, resulting in as rapid decay; and growths of a century, yielding oak and pine for thousands of houses on the prairies and by the seaside.

For richness of coloring, no scene save a grand sunset can compare with autumn woods. Well do I remember one October scene, a green field of wheat, beautifully green, walled on three sides with lofty maples in whose flushed leaves seemed fixed the beauties of a whole summer's sunsets, so gorgeous were they.

Again, there is in the forest always something new. The real lover of nature never sees two days, or two trees, and scarcely two flowers, exactly alike.

Enough of variety exists everywhere to make her attractions infinite.

To the botanist, even the gayest flowers are not more attractive than the majestic old trees. By chance he finds their odd blossoms, and admires.

He sees all the buds ready formed in the fall, and wonders that he never noticed it before. They are arranged, too, in perfect order, upon the maple and box elder they are opposite, in alternate pairs; upon the oak and plum, the first, sixth, eleventh, and sixteenth buds, counting from the base upward, are in a direct line, forming a row, and on each branch (if long enough) there will be five such rows.

Inspecting a branch of the black oak, the botanist learns to his surprise that it has, at the same time, fresh flowers, and acorns of a year's growth.

Watching until October, he sees the acorns ripen and fall, nearly thirty months from the time when they began to form in the bud. The acorns of the white oak ripen within six months from the death of the blossoms which gave rise to them.

There are other things small things in the woods, which we rarely notice. This moss grown log on which we rest is covered with them. The hundreds of rounded patches, greenish and gray and brown, growing on the bare flat surface, and the scores of little gray shafts with crimson caps, such are lichens, flowerless plants without distinct stems or leaves.

These delicate green plants, trailing along the crevices of the bark, and those erect in bunches, like miniature pine forests, are mosses, flowerless plants with stem and leaf distinct.

And now, like true lovers of nature, let us search for beauty; for when the green forest aisles in their wealth of dew and flowers and morning light have filled the mind with thoughts of God's perfect work, 'tis then the discovery of one more new and beautiful flower brings the overflowing tear of admiration.

GEO. R. AVERY.

Black Oak Tree