"STRAIGHTENING OUT FURROWS."

CAPTAIN CROFTS, or Cap'n Sam, as he was familiarly called, was a great favorite among the boys of Seaport. Who else would harness up the sturdy horse into a big wagon, and give them such grand rides? Then the great hickory and chest-nut trees at the foot of his lot were free for the boys to visit as often as they liked, only they must never damage in any way the fine old branches; and when it came to telling stories, it was hard to find his equal.

One day the boys, quite a little crowd of them, found Cap'n Sam on the rocks at the beach. There were breakers that afternoon, and at such times it was a favorite diversion of the seafaring man to sit high on the rocky beach, and listen to the sounding sea. On this particular afternoon the captain seemed to be thinking very soberly, and he couldn't throw off the mood, even at the approach of the merry boys.

At length, looking up from his brown study, the captain said, "Boys, do you know what I've been trying to do every day for the last ten years I've been trying, every day of my life, to straighten out furrows, and I can't do it."

One boy turned his head in surprise toward the captain's neatly kept place.

"Oh, I don't mean that kind, lad; I don't mean land furrows," answered the captain, so soberly that the attention of the boys became breathless as he went on:—

"When I was a lad about the age of you boys, I was what they called a 'hard case,'—not exactly bad or vicious, but wayward and wild. My dear mother used to coax, pray, and punish. My father was dead, which made it all the harder for her, but she never became impatient. How she bore with all my stubborn, vexing ways so patiently will always be a mystery to me. I knew my course was troubling her,—knew it was changing her pretty face, making it look anxious and old.

After a while, tiring of all restraint, I ran away,—went off to sea; and a rough time I had of it at first. Still I liked the water, and liked journeying around from place to place. Then I settled down to business in a foreign land, and soon be-came prosperous; now I began sending her something besides empty letters. And such beautiful letters as she wrote me during those years of cruel absence! At length I noticed how she longed for the presence of the son who used to try her so, and I determined to go back to her. And such a welcome as I received!

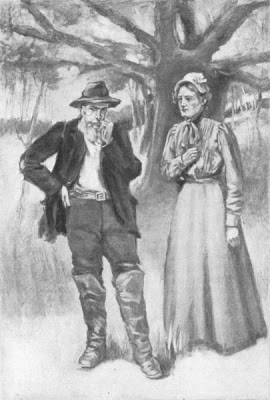

"My mother was not then a very old lady, boys; but the first thing I noticed was the whiteness of her hair, and the deep furrows on her brow; and I knew that I had helped blanch that hair to its snowy whiteness, and had drawn those lines in that smooth forehead. And those are the furrows I've been trying to straighten out.

"Last night, while mother was sleeping in her chair, I sat thinking it all over, and looked to see what progress I had made. Her face was very peaceful, and the expression as contented as possible; but the furrows were still there. I hadn't straightened them all out—and I never shall—never! When they lay my mother in her coffin, there will be furrows in her brow. Remember, lads, that the neglect you offer your parents' counsels now, and the trouble you cause them, will abide."

"But," broke in Freddie Hollis, with great troubled eyes, " I should think if you're kind and good now, it need n't matter so much."

"Ah, Freddie, my boy," said the quavery voice of the strong man, "you cannot undo the past.

You may do much to atone for it,—do much to make the rough path smooth ; but you cannot straighten out the old furrows, my laddies--remember that!"

"Guess I'll go and chop that wood mother spoke of," said lively Jimmy Hollis, in a strangely quiet tone for him.

"Yes, and I've got some errands to do," suddenly remembered Billy Bowles.

"Touched and taken," said the kindly captain to himself, as the boys trooped off, keeping step in a thoughtful, soldier-like way.

Harriet A. Cheever.

PRAYER should be the key of the day, and the lock of the night.